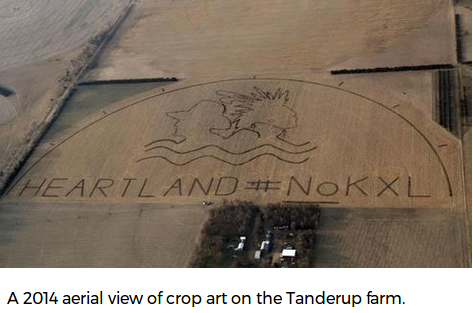

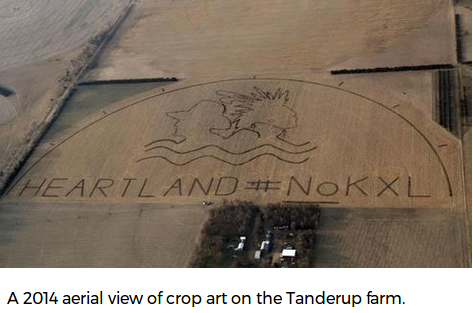

The organizing cohesiveness of BOLD Nebraska over the years to forge common ground between disparate socio-political interests fighting Keystone XL has been instructive and inspirational. While adjoining states, and U.S. officials alike, have had mixed success resisting the oilagarchy, the people of Nebraska have single handedly stopped TransCanada on multiple fronts – direct action, the courts, the Nebraska Public Service Commission, and creative actions like solar installations along the route of the pipeline. This kind of success can be achieved only by presenting a united front, united only due to mutual respect. The BOLD Nebraska folks, under Jane Kleeb’s guidance, listened to the concerns of conservative farmers and ranchers, school districts, water districts, and tradesmen to build an awareness of the pipeline’s likely impact on their livelihood. The learning curve has been methodical and steady, and has paid off when you read comments like this: “I think if not for Bold, the pipeline would be in today”, says Art Tanderup. Tanderup found that his 160 acre farm, that has been in his wife’s family for 101 years, is in Keystone’s way. “[Jane Kleeb] was the glue that kept us landowners together, and kept the organizing that happened in the state going.” Kleeb related this tale. “About two or three years into the fight, one of the farmers came up to me and asked if I had ever heard of the documentary ‘An Inconvenient Truth’. I started to laugh — I told him that indeed I had, but it’d been a while. And he was like, ‘Well, my daughter got me a Netflix subscription for Christmas, and I’ve been watching all of these documentaries on climate change, and man, we really should have been listening to Al Gore.'”

An article in Popular Science provides insight into the issues, the stakes, and the success of BOLD Nebraska. “Perhaps if TransCanada hadn’t first proposed to put the pipeline not only through a cherished region, but one that rests atop the state’s most precious resource, they would not have encountered such fierce resistance. But they did. And so from the beginning, as it were, the balances were not correct. Nebraskans really, really love their aquifer. Jane Kleeb noted,’There’s books, there’s songs, there’s poetry about the Ogallala Aquifer. We don’t have a ton of corporate agriculture in our state. It’s still family farms and ranches of people who homesteaded in the 1800s, still being run by those same families. Nebraska is kind of unique in that sense.

“‘Everything we do here is out of that aquifer’ says Tanderup, who grows mostly corn, soy, rye, and cover crops on his farm. ‘We drink it, the livestock drink it, we irrigate with it, and we water our gardens with it. It’s our water.’ John Hansen, President of Nebraska’s Farmers Union, believes that the Sandhills make for a risky shortcut. ‘Why would you run a pipeline in an area where, if it leaks, it goes right into the water supply?’

“Jim Carlson, who lives in Central Nebraska said ‘They came, knocked on my door, and offered me a pretty substantial amount of money’. That’s when he decided he should find out more about what was happening in his backyard. He learned that the oil will come from the tar sand fields of Alberta, Canada – a bitumin that isn’t liquid, but closer to the consistency of molasses. John Stansbury, an Associate Professor of Environmental Water Resources Engineering at the University of Nebraska said ‘a small leak from an underground rupture in the Sandhills could pollute almost 5 billion gallons of groundwater, if it went undetected. It’s important to note that when pipelines leak, the problem isn’t usually caught by high-tech leak detection systems. There are two problems with this. The first is that the bitumen sticks to everything — vegetation, rocks, riverbanks — and it’s not easily washed away. The second is that while conventional crude oil floats, bitumen sinks. In the end, knowing that, Carlson turned down a little more than $300,000 rather than allowing Keystone XL to come through his land.

“In August, Bold Nebraska (in coordination with 350.org, Indigenous Environmental Network, and a coalition of other groups) launched a $50,000 dollar crowdfunding effort to build solar installations inside the proposed pipeline route. Said Tanderup ‘My wife and I try to burn biodiesel, we try and burn ethanol, but we need to do more. We invested in a solar system for our farm’. The 91% of the farm’s kilowatt needs it generated last year wasn’t enough to satisfy them. ‘So, we bought an electric car, and we charge it off of the solar panels.’ Now that his eyes are open, Jim Carlson sees the signs of a warming climate all around him. Rising global temperatures make for an earlier spring. ‘We plant corn three weeks earlier than we used to’, he says.” Read more at – This land is (still) their land. Meet the Nebraskan farmers fighting Keystone XL.

Lawrence Kansas Native Erin Brockovich posted on social media about the proposed Tonganoxie, Kansas Tyson Slaughter House

“Mothers have sent me photographs of their children at the local baseball field just blocks from the location of the proposed slaughter house,”

She goes on to cite statistics about the company’s polluting record.

“Tyson Foods Inc. was the second biggest polluter of America’s waterways from 2010 to 2014, according to the most current data the company submitted to the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s (USEPA’s) Toxic Release Inventory. Ranking only behind AK Steel Holding Corp, Tyson Foods and its subsidiaries’ processing plants dumped more than 104 million pounds of pollutants into waterways over those five years – more than Cargill Inc., Koch Industries Inc., and ExxonMobil Corporation combined.”

My inbox is full of requests from the good people of Tonganoxie, Kansas asking for my help fighting a massive chicken…

Posted by Erin Brockovich on Thursday, September 7, 2017

Photo by: Chip Somodevilla

Stretched along the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana are some 840 petrochemical plants and refineries, as well as above-and-below ground oil storage tanks, and gas and oil export terminals. In addition, a large number of the more than 170 Texas Superfund sites are concentrated along the coast, 15 of which are in Houston alone. The floodwaters that covered the entire region have created a public health catastrophe that will persist long after the waters recede. Contributing factors are fecal coliform from swamped sewage treatment plants, molds growing in saturated structures, failure of some municipal water supply systems, inundated oil tank farms, leaking chemical plants and refineries, noxious plumes from fires, and the flooded Superfund sites – Harvey Aftermath: A Public Health Crisis in the Making.

There are quite a number of media stories about these various environmental disasters, but one of the more revealing views comes from the industry itself. A commercial group called Independent Chemical Information Service is the world’s largest petrochemical market information provider of pricing information, news, analysis and consulting to buyers, sellers and analysts. They examine in real time the status of supply and demand within 180 commodity markets, and their website has an interactive map to search for information on given products or companies. This map is very busy at the moment, with status reports on every business affected by Hurricane Harvey – Hurricane Harvey impact on the petrochemical markets (interactive map). You can view the entire Gulf Coast, zoom to a regional level, or to a city, or even down to neighborhood scale. Hover over the icon for a company, and see it’s status from a list including: shut down, reduced, restarting, operating, etc., and some disturbing categories such as “upset”, “closed”, and “force majeure”. “Force majeure” is a legal term, referring to a company’s inability to produce a product or service following a storm or other unanticipated event.

While floodwaters and storm winds may have affected the region as a whole, Harvey dumped most heavily on Houston proper. And in Houston, the worst effects are being felt by what are called “fence line” neighborhoods, or environmental justice (EJ) neighborhoods. The Union of Concerned Scientists reported that more than a million pounds of emissions from the oil refineries and chemical plants that border EJ communities have been released into the Houston air. Both common sense and real estate appraisal tell us that land nearby to polluting industries is of poor marketability, so it’s the poor who end up living there. In Houston, the toxic impacts are worse than anywhere else. Houston is the only major city in North America without land use zoning. While other U.S. cities might allow housing to be located somewhat near to industrial sites, in Houston, residential use is allowed immediately across the fence or street from industrial uses – fence line neighborhoods. These neighborhoods are predominantly low-income and ethnic minority areas. It’s no surprise that both polluting industries and EJ neighborhoods are clustered in east Houston. You may want to sign this petition to Congress – Harvey relief MUST address the needs of fenceline communities.

The UCS has paired up with one of the most active EJ groups in Houston – the Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (TEJAS) – TEJAS. Other groups such as the Houston Hip Hop Caucus are addressing the Harvey issues, but TEJAS has been central to EJ organizing for decades, during everyday living conditions and in crisis situations. TEJAS is notifying neighbors about toxic exposure safeguards, giving media interviews, and has filed a court motion to stop the EPA from delaying the Chemical Disaster Rule. Most notably, in response to the explosion and fire at the Arkema liquid organic peroxides factory in Crosby TX, TEJAS is urging nearby residents to evacuate, and pushing for full disclosure of the chemicals used in the facility. To donate to TEJAS, click this link – Donate to the TEJAS Harvey Fund, and be reassured it will go to disaster relief on the ground, not into the bureaucracy of a national agency.

On 31 August 2017, flooding interrupted electric supply to the Arkema peroxides plant. With no back-up power to keep storage tanks of chemicals refrigerated, rising temperatures triggered two spontaneous explosions. Fifteen police officers were taken to a hospital for inhaling fumes, while a 1.5-mile evacuation zone was imposed. Rather than allow the remaining tanks to reach explosive temperatures, on 2-3 September, the company staged “controlled ignition” of six more tanks (set them on fire), to “neutralize” the chemicals as the company described it – Evacuation zone around Arkema’s Texas plant lifted after controlled ignitions. TEJAS and UCS and others had demanded full disclosure of what was in the tanks, and what compounds would then be in the black smoke that neighbors would be breathing, but Arkema refused – (video) Smoke from chemical plant fires caused by Houston flood raises concerns, and As Arkema Plant Burns, Six Things We Know About Petrochemical Risks in the Wake of Harvey.

This report is just the tip of the iceburg. The UCS recommended these additional resources:

Some other sites for further reading are:

Recent Comments