SUSTAINABILITY ACTION ANNUAL MEETING AND SCREENING OF “BAG IT” FILM

Friday, 22 January 2021, 7:00pm

virtual Zoom meeting, Lawrence KS 66044

You are invited! The Sustainability Action Network annual meeting will feature an on-line screening of the film “Bag It”, about plastics pollution and banning the bag. The film is an hour and fifteen minutes. Following the film will be a open discussion of plastic pollution, and how to get the City of Lawrence to finally ban the bag.

Sustainability Action has been advancing ecological sustainability since 2007. We focus on helping individuals live a sustainable lifestyle, while pushing institutional policy change that can impact the broader population. We work in areas of renewable energy, healthy climate, local food and permaculture, multi-modal transportation, prime farm soils preservation, and ecosystem protection.

Some of our 2020 actions and accomplishments include:

- Along with collaborating groups, we got the City of Lawrence to commit to 100% renewable energy

- The bicycle boulevard we promoted got built on 21st Street

- We helped stop for the fourth time a mega-retail center in the 100-year floodplain of the Wakarusa Wetlands

- We got the City of Lawrence to negotiate with Black Hills Energy to provide renewable biogas in Lawrence

- We challenged Evergy’s transparency in their cleanup of Lawrence coal ash pits, and in their plans for shutting the Lawrence Energy Center coal plant

- We sent testimony to the Kansas Corporation Commission in opposition to Evergy’s discriminatory rooftop solar rate proposals

The meeting will also include: an introduction to our Board, a review of our 2020 accomplishments, an open discussion on projects for the upcoming year, a brief financial report, and Board of Directors election. To join the meeting, just click this Zoom link at the time – https://zoom.us/j/91950806764?pwd=TUpEdzdUNUtMMGN4UWpvVmRQQ2FIdz09. The passcode for entry is 137922.

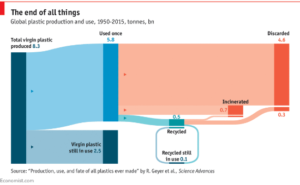

Scientists have estimated that, since 1950, humans have generated 9.1 billion tons (8.3 billion metric tonnes) of plastic. About 76% of that has ended its useful life and become waste. Of that 7 billion tons of waste, only 9% has been recycled, the rest going to landfills, being incinerated, or choking and poisoning streams and oceans. The U.S. alone produces on average 35.4 million tons of plastic (32 million metric tonnes) per year, according to the EPA – Humans Have Created 9 Billion Tons of Plastic Since 1950.

This is a far cry from the public relations narrative of recyclability. Because the U.S. lacks particular equipment and market interest, most types of plastic are not recyclable, only #1 and #2. And even so, only #1 plastic bottles are regularly recycled, according to a study by Greenpeace – U.S. Survey of Plastics Recyclability. The Greenpeace report said that plastics #3 through #7, called mixed plastic, are more difficult, more expensive, and more energy intensive to process than numbers 1 and 2. Most single-use retail bags are #4.

Speaking for the Association of Plastic Recyclers, Kara Pochiro, said “What the United States needs is infrastructure equipped to process other kinds of plastic”. But John Hocevar of Greenpeace emphasized a more basic and elegant solution, saying “The really simple answer is we have to stop making so much throwaway plastic” – How much plastic actually gets recycled?.

The unimaginably large amount of plastic materials comes with equally thorny problems:

But because humans enjoy many of the properties of plastics, many problems are either below the radar or purposely ignored for the benefit of petrochemical companies. Plastics are waterproof and lightweight. Clear plastic packaging is a great marketing tool. Plastics can be formed into virtually any shape (hence the name “plastic”). They make convenient items like paint and clothes and containers. But the biggest reason we tend to overlook the problems is because petrochemical PR has misled us.

An article by NPR and PBS reported that public officials, like most people, don’t want to be told the sad truth that only a tiny fraction of plastics can economically be recycled. Laura Leebrick, a well-intentioned but naive waste hauler, recounted telling a city council that it was costing more to recycle plastic than to dispose of it. They were in denial and said “You’re lying. This is gold. This is valuable”. But NPR explained “It’s not valuable, and it never has been. And what’s more, the makers of plastic — the nation’s largest oil and gas companies — have known this all along, even as they spent millions of dollars telling the American public the opposite”. One industry insider wrote in a 1974 speech “There is serious doubt that [recycling plastic] can ever be made viable on an economic basis”.

Regardless of the fact of the matter, the public was led to embrace recycling. NPR noted that back in the late 1980s, plastic was in a crisis because of too much plastic trash. The public was getting upset. The genius — and fraud — of the plastics industry was to convince the public that recycling was working. Starting in the 1990s, the public saw an increasing number of commercials and messaging about recycling plastic. When they believed the hype, they felt fine about buying more new plastic. This of course was the goal of Big Oil and Big Gas — more new plastic sold meant more profits.

Still, plastic recycling grew slowly. Recyclers were losing money when only soda bottles and milk jugs were brought in. The industry needed a new strategy. Oil and plastics executives began a quiet campaign to lobby almost 40 states to mandate that the triangular recycling symbol appear on all plastic, even if there was no way to economically recycle it. Some environmentalists also supported the symbol, thinking it would help separate plastic. It didn’t — it only made all plastic look recyclable.

With the various numbered recycling symbols, the industry succeeded in gaining widespread acceptance of recycling, even while knowing it is unfeasible. But it became a failure for recycling operators. People began throwing every kind of plastic into recycling bins, even though recyclers lost money on all but #1 and #2. Worse, it became a cost prohibitive sorting nightmare for the operators, but also for communities struggling with choosing source-separated recycling vs mixed-materials recycling. A lack of an industry standard further hampers recycling feasibility because of regional market irregularities, and because of recycling truck and equipment disparities – How Big Oil Misled The Public Into Believing Plastic Would Be Recycled.

Plastic recycling was never intended to work to any degree. Attempts by local communities, retailers, recycling operators, and materials marketers to find a way to make it work were random and mostly on their own. Big Oil and Gas were the only winners. Now with the nose-dive of gasoline and diesel sales, and communities beginning to ban natural gas for all-electric buildings, Big Oil and Gas are shifting their focus to increase plastic production – Big Oil’s hopes are pinned on plastics. It won’t end well.

A large part of their plan is to flood Africa with plastics as an untapped market. Currently 34 of the 54 African countries have committed to phasing out single-use plastic. The lobby group pushing to open up Africa, the American Chemistry Council, has members including Shell, Exxon and Total – Oil-backed trade group is lobbying the Trump administration to push plastics across Africa. The industry mantra has not changed from advice given to Dustin Hoffman in the 1970 film “The Graduate” – In a word, plastics: The Graduate – YouTube.

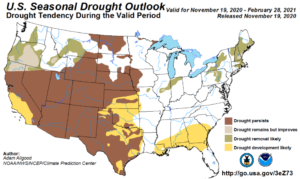

Possibly more than any other climate catastrophe is the specter of drought. It is true that a hotter climate pumps more moisture into the atmosphere, and does bring more rain. But the extreme climate fluctuations cause more severe storms not necessarily where rain is needed. By the same token, more severe drought is tending to scorch areas where rainfall has diminished. Storms and flooding certainly can inflict immediate destruction, but drought desiccates entire regions for extended periods, killing ecosystems and economic systems both.

As drought is becoming more widespread – in the Pacific Northwest, the Amazon basin, Central America, the Sahel in Africa, Mongolia – a recent study published in Science Advances is predicting a 21st Century drought in the U.S. southwest and the High Plains, possibly for 100 years – US faces worst droughts in 1,000 years, predict scientists.

The Ogallala Aquifer, also known as the High Plains Aquifer, underlies an estimated 174,000 square miles of the Central Plains, mostly under Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, but also areas in New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and South Dakota. The Ogallala is one of the largest underground freshwater sources in the world, holding as much water as Lake Huron. These agricultural states are already experiencing drought, prompting farmers to pump the Ogallala Aquifer at an alarming rate.

But as 60 years of pumping have pulled groundwater levels down by scores of feet, as much as 250 feet in southwest Kansas, most of the creeks and rivers that once veined the land have dried up. Throughout the 20th Century, the US Geological Survey estimates irrigation depleted the aquifer by 253 million acre-feet, about nine percent of its total volume. The Denver Post analyzed federal data and found that the aquifer shrank twice as fast from 2011 through 2017 as it had over the previous 60 years.

This is not sustainable. Considering the drought, some options are to switch from growing very thirsty corn to more dryland crops like winter wheat, beans, or sunflowers, to rely less on cornfed feedlot cattle, and to adopt no-till methods plus cover crops. But all the same, it still comes down to water. To address the depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer, two counties in far west-central Kansas are exploring natural ways of recharging the aquifer.

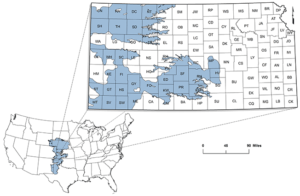

An initiative begun in 2016 by the Wichita County Water Conservation Area (WCA) has been awarded $1.4 million by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to study how playa wetland lakes can help recharge the Ogallala – NRCS Awards $1.4 Million to Support Local Water Sustainability Project. Partnering in this effort will be Greely County Conservation District, the Kansas Association of Conservation Districts, the Playa Lakes Joint Venture, and Ducks Unlimited, in a program called the Groundwater Recharge and Sustainability Project (GRASP).

Playas are shallow, circular-shaped wetlands that are primarily filled by rainfall, although some playas found in cropland settings may also receive water from irrigation runoff. Some think that playas are carved by wind, but it’s more likely they are formed by land subsidence – in other words, sinkholes. Playas are ephemeral, filling only from Spring rainfall, and the average size being 3.7 acres. Recent research has revealed that water provided by playa wetlands adds three inches to the level of the Ogallala aquifer each year – Playas – Ephemeral Wetlands of the Great Plains – KU Aquatic Ecology Lab.

According to Abe Lollar, a biologist with Ducks Unlimited, native prairie shortgrass seed mixes are a necessary part of the playa restoration process. The planted grass buffer acts like a natural water filter. Rainwater from surrounding fields runs into the playa and carries sediment and contaminants with it. The shortgrass will stop much of the sediment from entering the playa and improve the quality of the water entering the aquifer. It will also provide habitat and a food source for birds and pollinators.

Playa lakes are arguably the most significant ecological feature in the High Plains, even though they cover only 2 percent of the region’s landscape. Supposedly there are more than 80,000 playas scattered across the Great Plains. The Kansas Geological Survey reported that varied estimates put the number of High Plains playas between 25,000 and 60,000. However University of Kansas researchers recently identified more than 22,000 in Kansas alone. No one has ever tried to count them all – Playas in Kansas and the High Plains.

Recent Comments